I don’t know Gary Shteyngart, but I’ve met him a few times in passing. In each case I was tongue-tied and desperate to remind him I’d written a few science fiction columns on how I think he’s tops. He always smiled shyly, right before making some outrageous statement like: “I should have all the Hugos!”

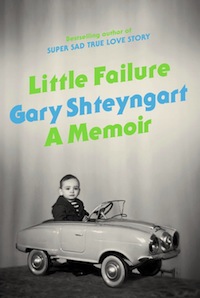

This one-two punch of self-deprecation with confident hyperbole is not just limited to real-life interaction, but it’s what makes a Shteyngart book a Shteyngart book. And his newest—a memoir titled Little Failure—is no different. Back in the spring of 2012, in a brief correspondence with Gary, I asked him if what he was working on would have science fiction stuff in it like Super Sad True Love Story. His swift response: “It’s a memoir about my childhood. So yeah. Science fiction all the way.”

There are probably some (all six of you who read this column) who are sick to death of me claiming any old book under our hot yellow sun is “science fiction” just because I feel like having a complex game of semantics combined with comparative literature from another dimension. So, don’t worry. I’m not claiming an actual memoir, a work of non-fiction (from a Columbia professor no less!) as a work of science fiction. If the whole thing turns out that Gary Shteyngart is pulling a Million Little Pieces on us and the contents of all of his book trailers are his true biography, then, and only then will Little Failure be rendered a science fiction novel.

But as a memoir, it lands a few times on a subject close to probably many of our hearts: how science fiction can rescue a child from the real world. A good chunk of Little Failure details the author’s recollections of growing up in Russia and emigrating to the United States, and throughout all of it, Gary Shteyngart comes across as something of a stranger in a strange land, a space alien, somehow alone among his own kind. In describing Moscow Square and the Russian language itself he writes this:

“And the words! Those words whose power seems not only persuasive but, to a kid about to become obsessed with science fiction, they are indeed extraterrestrial. The wise aliens have landed and WE ARE THEM.”

For lack of better words (Shteyngart finds them in his memoir!) he’s a strange, small child who seems to feel loved by his parents but lonely simultaneously. The act of moving from Leningrad to Queens, NY is also not necessarily easy, and Shteyngart peppers all of this, gradually with the fact that his younger self loved science fiction. He even describes the plot his first novel—written at five years old—which features a giant flying/talking/treacherous goose who teams up with superhero version of Vladimir Lenin, who in turn, suspiciously shares the young’s writer’s affliction with asthma. We also get a quick education about a 1970’s Russian sci-fi program called Planet Andromeda, which later inspires the author to imagine adventures of good rockets and bad rockets, both of which seem to haunt him like angels and devils on opposing shoulders.

From his obsessive reading of Asimov’s Science Fiction, to his “crush” on Erin Gray’s Col. Wilma Deering in the 70’s Buck Rogers to his young political analysis of Planet of the Apes: (“If Charlton Heston is a Republican, are the monkeys soviets?”) the first half of Little Failure gestures at a boy leaning on science fiction not so much as a crutch, but as a kind of kaleidoscope-colored glasses, adjusting his vision to filter out pain.

There’s a lot to take away from Little Failure, but on the front of science fiction, it mainly caused me to reflect on my own obsessions with the genre as a child and how closely connected a love of science fiction is with the a feeling an outsider or “the other” as a child. Sure, sure, anyone who puts pen-to-paper or fingers to keys is some kind of disaffected weirdo (I can’t imagine many popular jocks from my high school turning into hot-shit writers or artists) but there seems to be an extra level of isolation with the young science fiction addict.

Shteyngart writes in detail about his crippling asthma as a child, which alone, is terrifying, but when he describes the barbarian and totally outdated “treatment” of “cupping” preformed on this poor young back, it sounds like the kind of torture only a Cardassian would dream up. The rockets and the aliens and Wilma Deering then, become our helping hands as children. Our distractions from the terribleness of being young and alone.

I can distinctly recall being 6-years-old and deciding which crew member from the original Star Trek was my closest friend. Not my favorite (Spock!) but my closest friend. Being something of a realist, I suppose I determined my closet friend on the original U.S.S. Enterprise was Pavel Chekov, the faux-Russian. I think I selected him because he was the youngest and he seemed like an outcast, too. He also screamed a lot, which seemed like the kind of thing I would do if I was in space. As an adult, I kind of hated Chekhov, but something in Little Failure (maybe the childhood sci-fi angst, but probably all the Russian words) made me appreciate that imaginary childhood friendship again.

In one of his outrageous book trailers for 2010’s Super Sad True Love Story, Shteyngart pretends to confuse Anton Chekhov with Pavel Chekov, by saying “guy from Star Trek writes books?” But, with Little Failure, I wonder if maybe Gary Shteyngart himself isn’t that guy from Star Trek, who yes, writes very, very good books.

Ryan Britt is a longtime and (Baker Street) irregular contributor to Tor.com. He was briefly in a movie with Gary Shteyngart, though neither spoke, nor share the same exact scene. But Shteyngart spit on someone and Ryan read a Ray Bradbury story in the background. True facts.